Since Hawai’i is the most remote landmass on the globe, the state has a large number of endemic or indigenous birds. Many of these birds you will see nowhere else on earth. These birds survive and can thrive primarily due to their many endemic food sources – plants and flowers found only in Hawai’i.

For dedicated birders, who want to experience and learn about Hawaii’s endemic birds, Hawai’i has its own Annual Hawai’i Island Festival of Birds.

The 5th and most recent festival occurred virtually, October 15-19, 2020.

Besides including guided field trips and pelagic boat tours, this day-long Bird Fair includes:

- Educational booths

- Local arts and crafts

- Educational talks

- Panel discussions

- A special treat of an evening event of The Seabirds of Traditional Hawaiian Navigation

One of the downsides of Hawaii’s remote location is that the islands have a large number of extinct and endangered birds. This is caused by the introduction of humans, mammals, mosquitoes, and the loss of native habitat and food source plants, among other things.

The remaining 34 endemic birds paint a beautiful testament to the creative process on these incredible islands.

At one time, there were 56 species of ground nesting Hawaiian Honeycreepers. Of the 18 remaining, the top of the ABA’s Life List is Hawaii’s most striking Honeycreeper:

`I`iwi – Scarlet Honeycreeper (Ee-ee-vee)

Of the Hawaiian Honeycreepers, the ‘I’iwi is one of the most spectacular of Hawaiian birds. It has vermilion plumage, black wings and tail, and a long, de-curved bill; a bill which curves downwards to retrieve flower nectar.

Amazingly, all of these native Honeycreeper birds evolved in Hawai’i from a single finch-like ancestor!

‘I’iwi are well known for their long flights over the forests in search of lehua flowers, blooming on ‘Ohia trees, which are their primary food source.

They are typically found in high-elevation forests above 4,500 feet. Fortunately for the bird’s survival, the mosquitoes that transmit avian malaria and avian pox are less common at the higher elevations.

Juvenile birds have golden plumage and ivory bills. They can be a bit spotty and were mistaken for a different species by early naturalists.

‘Apapane (Ah-pah-pah-nay)

‘Apapane is the most abundant of the Hawaiian Honeycreepers with an incredibly gorgeous, diverse array of warbling, burbling, and whistling songs and calls which vary between the islands. This bird is a true songbird that is highly recognizable.

Listen to the Song of the ‘Apapane HERE

Residing in higher elevation forests, the ‘Apapane is smaller than the I’iwi. It has bright crimson plumage, black wings, and a smaller de-curved bill, making them easy to identify.

You can often see the ‘Apapane family together in February through mid-summer. The juvenile birds’ feathers do not turn red until they are ready to be on their own, at about 4 months old. These days you can find their nest on the edge of branches, which helps protect them from predators.

Pueo (poo-eh-oh)

The Pueo is also on the ABA’s Life List. This is Hawaii’s endemic Owl. It is a subspecies of the short-eared Owl. It is a special moment when one sees the Pueo cruising silently at twilight as it listens and watches for its prey down below and then suddenly swoops towards the ground.

They usually hunt in the mornings and late afternoons up to twilight. This is an opposite pattern to other species of owls. It was primarily because there were no night moving creatures in Hawai’i until the introduction of rats and mice.

Males perform aerial displays to attract mates, called sky dancing. Unfortunately, they are ground nesters, which makes their eggs and their young susceptible to introduced predators like mongoose.

The females are responsible for the brood, and it is the males’ responsibility to hunt, bring back the food, and defend the nest. The chicks hatch one at a time to avoid competition for food and usually leave the nest at about 2 months of age.

Unfortunately, they are strongly affected by light pollution and have been known to fly towards car headlights if they are out too long after sunset.

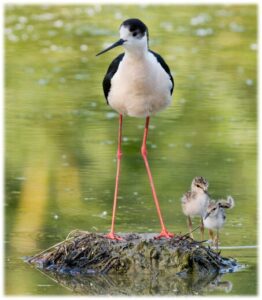

Ae’o (eye-oh)

The endangered Hawaiian stilt is a subspecies of the black-necked stilt. A long-legged shorebird with a long slender beak, also called the Kukuluae’o in Hawaiian. It is wonderful to see these lovely birds, walking in the shallow waters on their long stilt legs, hunting for food. You can often see them in the shallow brackish marshlands of Kanaha Pond State Wildlife Sanctuary along with several other endemic birds.

The adults aggressively defend their nests and young from potential predators. Watch out, stay back! They will charge!

Nēnē (Hawaiian Goose) (nay-nay)

If you visit the summit of Haleakala on Maui, you will most likely catch sight of the Nēnē, the State Bird of Hawai’i. This bird is also on the ABA’s Life List.

The black head and furrowed cream neck of the endangered Nēnē might look familiar. That’s because they are descended from Canadian Geese that made their way to Hawai’i one million years ago. Over time, those birds shrunk in size and grew proportionally longer legs with less webbing between their toes—adaptations that allowed them to easily navigate Hawaii’s lava fields.

A fabulous place to see and hear the Nēnē is the Paliku area at the eastern end of the crater on Haleakalā. In the twilight before a full moon night, you can watch and listen to these magnificent birds as they circle above Paliku, honking as they fly. It sure looks like the male is chasing the female. But to get to Paliku, you will need to hike 10.5 miles or rent some horses and stay overnight there. Ahhhh… yet another piece of paradise!

As unique and treasured as each of the Hawaiian Islands is, the birds are a big part of what makes this land so sweet and delightful.

Those lucky humans who get to control the invasive species in the nature reserves, such as Haleakalā National Park, often say that they can tell an endemic bird by the gentle, soft and plaintive tone of their calls. Much like the original settlers, the Hawaiian people also value being quiet, humble, and gentle.

The islands seem to have a power or energy which softens and sweetens almost everything upon them. Probably one of the many reasons people from around the world love to come here and soak in the calming, healing vibes. The vibrations of Aloha.

Writing and Graphic Design by Sugandha Ferro Black

Many thanks to the Audubon Society for their great Life List and info from the American Birders Association.

And to the USFWS for the Nene Image/Public Domain

Photos courtesy of paid for and other free sources unless otherwise noted.

Hawaiian Stilt | © CCO Alan Schmierer/Wiki, Hawaiian Owl | © CC BY 3.0 Forest and Kim Starr, I’iwi | © CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 Bryon Chin/Flickr, ‘Apapane | Public Domain, Young I’iwi | © CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 Bryon Chin/Flickr